The story of jobs in Massachusetts is a complex one. Just a year ago, the state’s economy roared, the unemployment rate scraped below 3%, and experts assured that if a recession was coming, it wouldn’t be anytime soon. And then came COVID-19. The virus that first made landfall in Massachusetts last February has since claimed the life of the 13,000 residents while the state has endured a series of stay at-home advisories, work from home mandates and school closures. But what does it all mean for job growth?

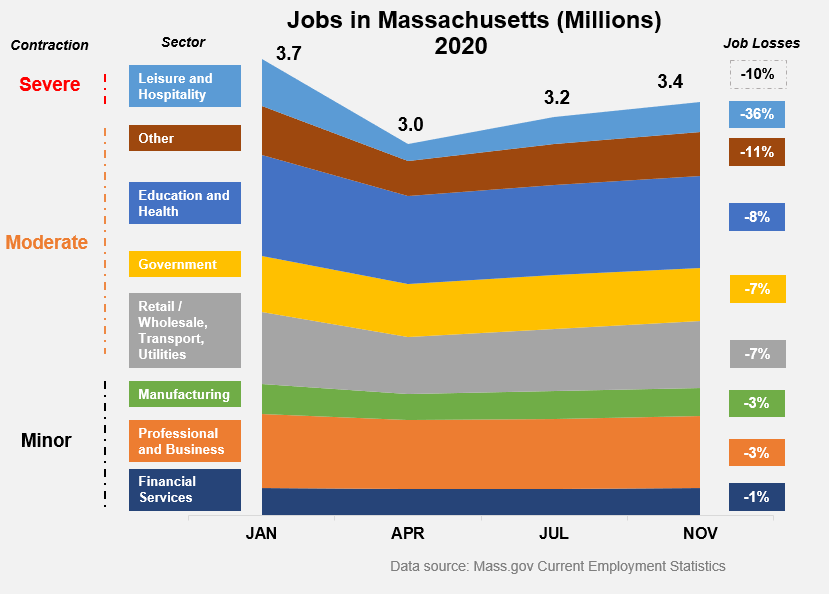

The year 2020 was an ugly one for the economy, and April was particularly horrific. The unemployment rate jumped six-fold from 2.8% to 16.2% as layoffs spread rapidly across the state. Spring brought promise and healing, however. The weather warmed, the virus retreated and Governor Charlie Baker initiated his four-phase reopening plan in May. From May through September, Massachusetts added an average of 64,000 jobs per month. Unfortunately, the recovery is not over. Fall and winter have coincided with a spike in infections, the pace of hiring has slowed, and the degree of economic hardship varies widely across walks of life.

The economic impact of COVID-19 on Massachusetts is a tale of two Commonwealths. There are those who endure the pandemic’s pain, and those who do not. Oft-discussed “white collar workers”—those occupying financial, managerial and business services roles, which account for a quarter of jobs across the state—have been largely insulated against the downturn. The digital nature of desk jobs has only accelerated during the pandemic thanks to the adoption of connectivity tools like Zoom. Manufacturing jobs also rebounded strongly during the summer, and the sector is just 7,000 jobs shy of its pre-COVID employment total. Other corners of the economy haven’t been so lucky.

Education and healthcare, classified as a single industry by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, employs 1 in 5 Massachusetts workers, but shed 8% of its workforce during 2020. A slow bounce back in healthcare has been partially offset by education jobs, which have remained stubbornly flat following a 13% paring in April. The number of retail and wholesaler jobs in the state remains 7% below its January 2020 peak; employment gains plateaued this fall following strong hiring in the spring and summer. State and local government jobs in the Commonwealth remain off by 7% from last year’s highs; the dip, likely lasting, is driven in part by closure of 2020 Census efforts.

Leisure and hospitality, which includes Boston’s cherished dining scene, along with the vibrant arts and entertainment community, sits in a tier of economic misery on its own. The industry, which employed 380,000 residents early last year, was forced to lay off a staggering 75% of its workforce during March and April, as dining and travel restrictions came to bear against a surging virus. Over a third of leisure and hospitality workers remain unemployed even after proprietors reupped staffing through the spring and summer. The Massachusetts Restaurant Association estimated in September that 20% of the state’s eateries have closed permanently.

The passage of recent bills in the Statehouse provides some support. In November, Governor Baker announced a $50 million economic stimulus providing relief to roughly 900 small businesses. The program received ten times as many applications. In December, Massachusetts announced a second stimulus for small businesses totaling $670 million. The latest measure, which allocates $75,000 per company, or three months’ expenses, could provide relief to nearly 9,000 businesses across the state. A balanced approach to grantmaking that views businesses through the lens of hardship while considering the company’s potential contributions to the economy is critical to maximizing the impact of the funds.

But the question remains: when will the economy go back to normal? The Massachusetts unemployment rate sits at 7% heading into the middle of winter, as the number of COVID cases remains elevated following the holidays. Assuming that hiring remains modest through the winter—10,000 jobs per month—and job gains in the spring and summer mirror those from last year as the vaccine is distributed and the state returns to a typical cadence of life—60,00 jobs per month—the Commonwealth can expect to return to pre-COVID employment levels sometime in the late summer. And for the many months in between, the degree of economic pain felt by those in the Bay State rests largely on occupation.

//

Matthew Doyle is a business development manager at L3Harris Technologies in Somerville and a graduate of the University of Rhode Island. His writing on business and the economy has appeared in The Providence Journal, Providence Business News, and The Day. Views expressed in his writing are his own. Follow him on Twitter @MatthewJDoyle_.